Forensic Fingering: Part One

Much can be learned by looking at fingering problems and practices in the context of the literature in which they occur. If consistent practices are found, one can evaluate these practices, discard some, modify some, and take advantage of others.

Introduction to the Series

When guitarists try to set down general rules or advice about fingering, they often end up offering guidance that is more constricting than enlightening. Some of the things I’ve heard have been statements such as, “Whenever possible, finger Bach in the lower position,” “Try to play melody notes on the same string,” “Shift on the strong beats,” “Never repeat a right-hand finger,” and so on. Students who adhere to these precepts often find themselves in a mental cul-de-sac as they attempt to follow these “rules.”

Guitarist Ronald Sherrod presents several lists of “fingering principles” in his 1981 dissertation, “A Guide to the Fingering of Music for the Guitar.”[1] At the end of the chapter on “Left-Hand Fingering: Melodies on a Single String,” for example, Sherrod presents the following “principles”:[2]

- Basic left-hand position should be utilized.

- For any melody, the smallest number of shifts necessary to play that melody should be used.

- For any melody, shift only as far as necessary to play that melody.

- Guide fingers should be utilized when changes of position are required.

- When shifts are required, the music should be analyzed in terms of expression and phrasing in order that the fingering corresponds to the musical thought.

- Strong finger combinations instead of weak ones should be utilized.

Additional “principles” are given at the end of the chapters exploring “Left-Hand Fingering: Homophonic and Contrapuntal Music” and “Right-Hand Fingering.” Sherrod states that, “This dissertation supplies the teacher with a theoretical basis from which to present this important topic.”[3] Sherrod’s theoretical basis is built upon the physical properties of the guitar and the physiological structure of the hand.[4]

At its highest level, though, fingering has always been the result of one’s musical creativity, technical proficiency, and how the latter can best express the former. Rarely are students given models about how to use fingerings to enhance their artistry.

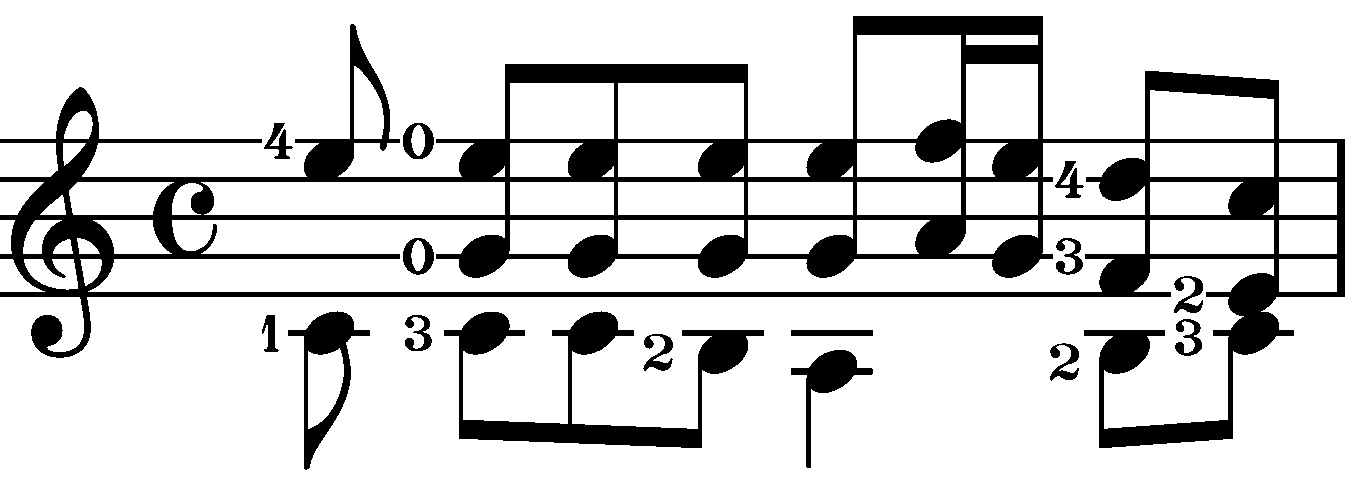

Consider this example from measure 63 of J. S. Bach’s Fugue, BWV 1000:[5]

Measure 63 of J. S. Bach, BWV 1000

The movement between the two chords on the last beat of the measure can easily sound choppy and disconnected. But if one keeps the fourth finger on D while fingers 2 and 3 move before the end of their notated value, the upper voice will be legato. If one voice is connected, the ear will perceive the whole as connected. This is an example of an artistic quality inhering in how one executes a fingering; the fingering may enable one to create a musical nuance, but the nuance won’t occur unless one knows how to achieve it.[6] This is at odds with the advice given by Carcassi, Aguado, Pascal Roch, and Emilio Pujol about moving from chord to chord in their influential method books. I will not discuss their advice here because I write about it in the post “Giuliani Revisited: Part Two” on The Guitar Whisperer Blog and on pages 143–146 of The Classical Guitar Companion.

There’s an additional element relevant to our work as concert guitarists: different eras had differing fingering practices. In most cases, these practices were well-suited to the music of the time and work well on the modern guitar. These earlier approaches to left and right-hand fingering represent a union of technical practicality, technical fluency, and musical expressivity. They shouldn’t be viewed as an inferior or less-evolved version of modern practices, as one might be tempted to do when comparing, say, 19th-century dentistry with dentistry today.

Well-trained guitarists should have an understanding of the fingering practices of composer-performers who have gone before. For example, I approach left- and right-hand fingerings differently according to the era of the composition and known fingering practices of the composer. An explanation of these earlier practices and the reasons behind them will be explored in future posts in this series. I’ve found that in some instances, historic fingering practices take advantage of the capabilities of the hands and fingers and help one achieve technical brilliance and musical refinement.[7] If one can escape viewing the past through the small portal of modern experience, some historic practices yield unexpectedly good results.

It is constraining to approach this complex topic with prescriptive and proscriptive “rules” in hand. I write “complex” because of all the interlocking components that inform one’s fingering decisions. One’s fingering is the result of one’s technical understanding, musical creativity, and awareness of historic practices. Fingering is not the generator of musical ideas, but good fingering allows one to express better one’s interpretive vision. If one’s interpretive vision is undeveloped, as is true for many students, then a perceptive teacher and good editions are essential.

Guitarists often invoke “personal preference” when discussing fingering, but it’s not always easy to tell the difference between a well-reasoned preference and an intractable habit masquerading as a personal preference.

Why Discussing Guitar Technique is Different from Buying a Sweater

Detailed explanations of things related to music, technique (which includes fingering), and interpretation are often described in terms of “personal preference.” This implies that there are things that have been tried and are not preferred. For example, a player with long fingernails cannot say, “I prefer long nails,” unless he or she has explored playing with shorter nails for enough time to be unaffected by the earlier habit. (The subject of nails is also complex because of the relationship between hand position and nail length: changes in nail length will often require an adjustment of right-hand position.)

This leads to the question, “Whence comes one’s preferences?” Might the “preferred” really be a habit in disguise?

However, if one has experimented, say, with strings of varying tensions over the course of time—and perhaps periodically during one’s career—one can accurately say, “I prefer to play with medium tension strings.” But this statement has a long way to go before it is useful to others unless it is followed by a clause that begins with the word “because.”

It’s not like going shopping with your mother and saying, “I prefer the blue one,” when she holds up two sweaters, one blue and the other green. One’s favorite color needs no justification or explanation. But if you’re a fashion designer—and not merely a consumer—who is charged with explaining why blue sweaters sell better, more is required of you.

Forensic Fingering

I use the word “forensic” to denote the importance of looking at evidence, by which is meant past practices or the editorial decisions made by performers who produce editions. The term is not an attempt to pretend we’re dealing with a science. Much can be learned by looking at fingering problems and practices in the context of the literature in which they occur. If consistent practices are found, one can evaluate these practices, discard some, modify some, and take advantage of others. Useful theories and guidelines come after examining practices.

For the first installment of this multi-part series, I’ll look at what I’ve termed “The Segovia Code,” which accounts for Segovia’s approach to right-hand fingering in scale passages.

The Segovia Code

When I was a student, the left and right-hand fingerings in Andrés Segovia’s editions were often regarded as illogical and idiosyncratic, although many guitarists of earlier generations regarded them as sacrosanct. John Duarte no doubt had Segovia in mind when he wrote in 1982 that, “simple commonsense suggests that similar phrases, especially when they are sequential, should be articulated in the same way unless there is a very good reason why they should not.”[8] Although Duarte’s article dealt specifically with guitar transcriptions of music by J. S. Bach, many guitarists have sought the uniformity important to Duarte in other repertoires. Duarte also writes, “Where ‘rhyming’ passages cannot be consistently articulated with slurs, it is usually better to play them without, letting the mind and fingers alone shape them.”[9]

However, there was a logic to Segovia’s fingerings and articulations, even in those passages for which Segovia didn’t indicate any right-hand fingerings. Segovia’s choice of left-hand fingering, which includes his use of slurs, was frequently made to ensure a convenient right-hand fingering. To my knowledge, Segovia never explained how he approached fingering, and perhaps his approach was obvious to guitarists who came of age in the early twentieth century and there was no need to articulate it.

Let’s look at some examples of Segovia’s “illogical” fingerings to see if there is a hidden logic to them. This is not to suggest that today’s guitarists should blindly follow Segovia’s fingerings for works that were written for him and for which he produced editions, but neither should his fingerings be blindly discarded before one understands them. This leads us to “Chesterton’s Fence.”

Chesterton’s Fence

There is a heuristic known as “Chesterton’s Fence.” Put simply, it states that it’s unwise to knock down a fence (or institution, or custom) unless you understand why it was put there in the first place. As G. K. Chesterton wrote in 1929:[10]

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Chesterton is not condemning those who want to change things, but he is asking us to understand the reasons behind the decisions of those who came before us. Unless we understand these reasons, we shouldn’t conclude that a decision is wrong. If we do not know how our modifications might affect other components of a thing, we might experience unintended consequences.

With this in mind, let’s look at several scale passages fingered by Segovia in the works of Joaquin Turina, Manuel Ponce, and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco.

Segovia’s Scale Fingerings in Literature

Although Andrés Segovia performed and recorded many works that contain scale passages, the works for which there exist fingered, published editions by him are a subset of the pieces that were composed for him. Some works written for Segovia were published without any fingerings at all. For example, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Concerto in D, Op. 99, which was published by Schott in 1939, contains neither left nor right-hand fingerings.

When Segovia did exercise his role as editor in music by Manuel Ponce, Federico Moreno-Torroba, Joaquin Turina, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and others, he gave more attention to left-hand fingering than he did to right-hand fingering. Joaquin Turina’s Fandanguillo, published by Schott in 1926, contains detailed fingerings for the left hand, but there are no right-hand fingerings at all.

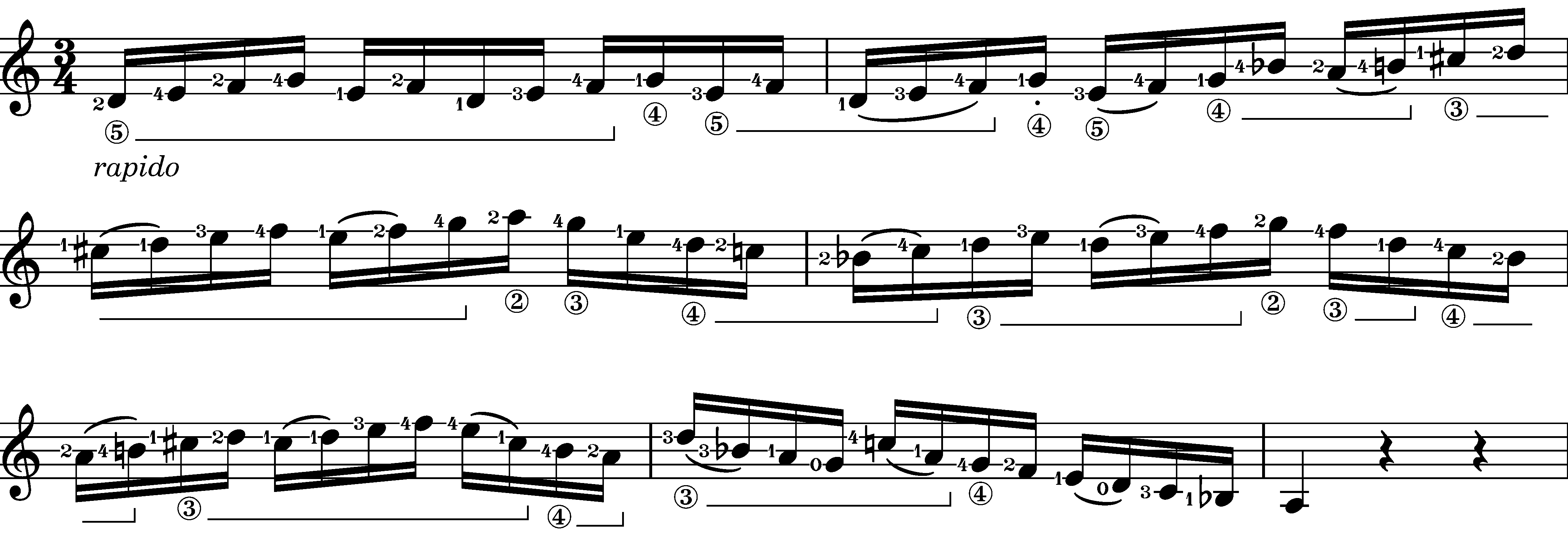

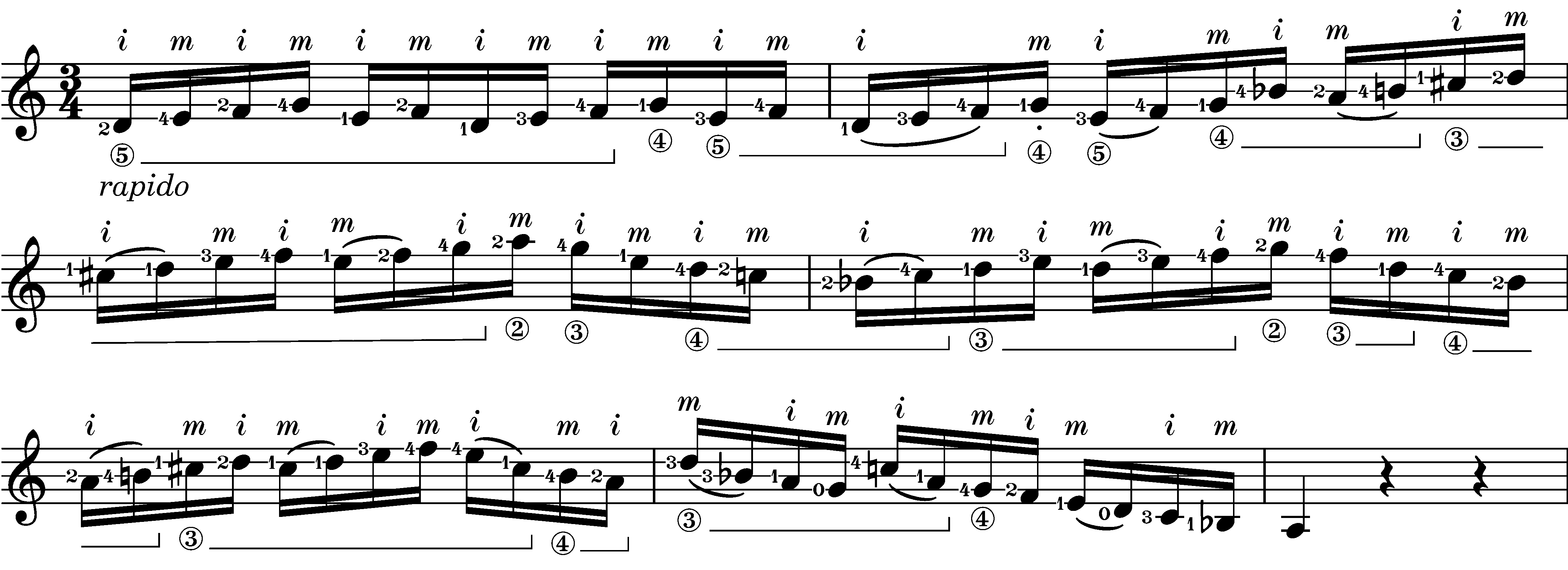

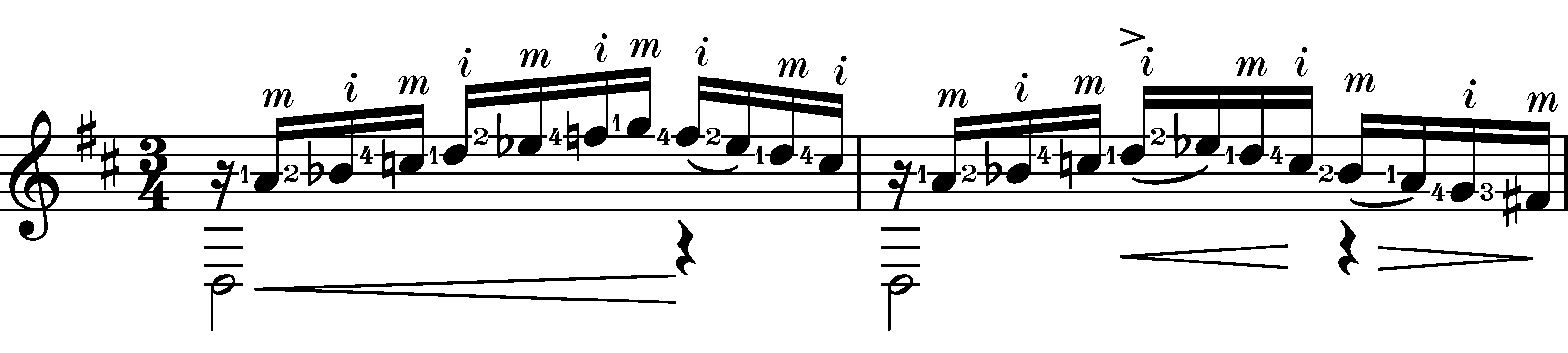

Below is a six-bar scale passage from Turina’s Fandanguillo. Segovia’s left-hand fingering is as it appears in the Schott edition.[11] Of special interest is the three-note slur in measure 75:

Turina: mm. 74–80, Fandanguillo, Op. 36

If one begins the scale passage with the index finger and follows Segovia’s left-hand fingering, the ascending string crosses will be made with the middle finger and descending string crosses will be made with the index finger. There are exceptions on the third beat of measure 78 and the second beat of measure 79, which require one to cross down with the middle finger, but these occur after a slur, which provides plenty of time for the string cross. Below is the same passage with right-hand fingering:

Turina: mm. 74–80, Fandanguillo, Op. 36 with right-hand fingering

If one changes the left-hand fingering, the passage becomes more difficult because of the awkward string crosses. (That said, I finger the first six notes of measure 74 with the left-hand the same way the last six notes are fingered, but this change doesn’t affect the string crossing.)

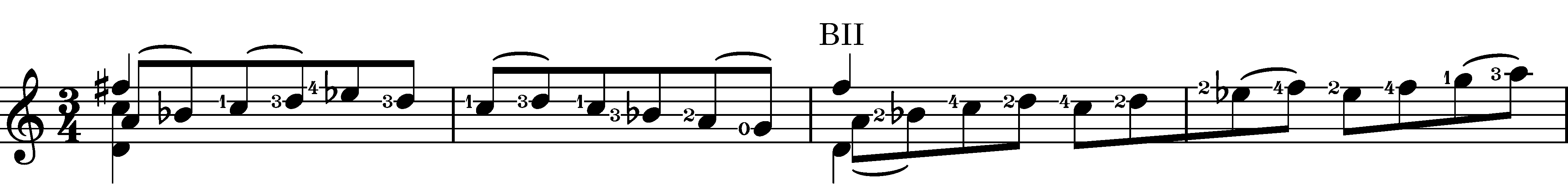

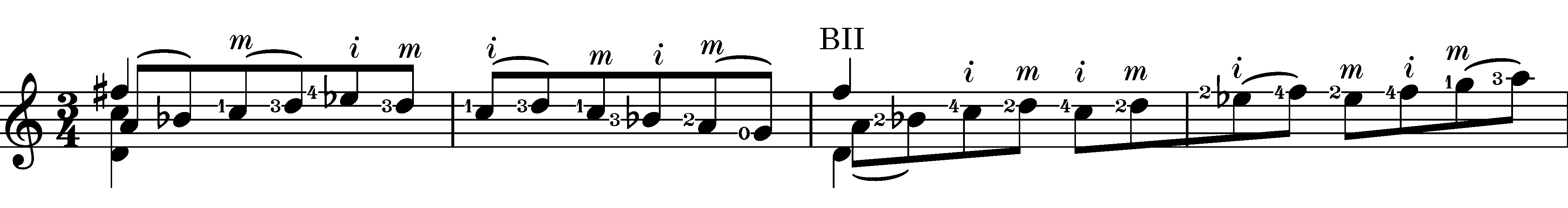

Manuel Ponce’s Sonata Three was published the following year. In the third movement, we see the same approach to fingering. Below are measures 80 and 81 as they appear in the 1927 Schott edition. As with the Turina Fandanguillo, no right-hand fingerings are given in these two measures. The tempo is Vivo:

Ponce: mm. 80–81, third movement from Sonata Three

If one begins these two short runs with the middle finger, the two descending string crosses can be performed with the index finger:

Ponce: mm. 80–81, third movement from Sonata Three with right-hand fingering

We see a similar approach in measures 96–99 in the second movement of Turina’s Homage à Tarrega. The tempo is Allegro vivo:

Turina: mm. 96–99, “Soleares” from Homage à Tarrega, Op. 69

If one begins the scale passage with the middle finger (after the first slur), all of the string crosses will fall under the fingers (i.e., ascending crosses with m and descending crosses with i):

Turina: mm. 96–99, “Soleares” from Homage à Tarrega, Op. 69 with right-hand fingering

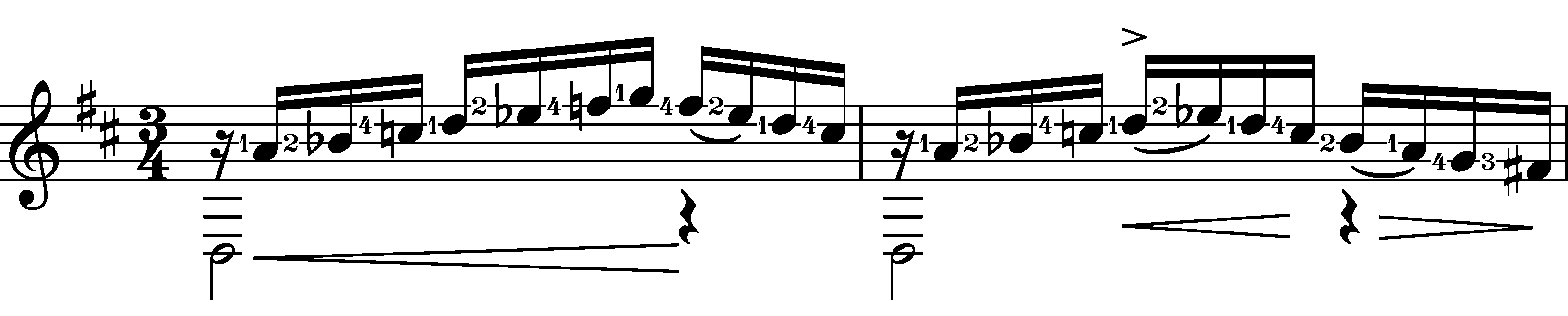

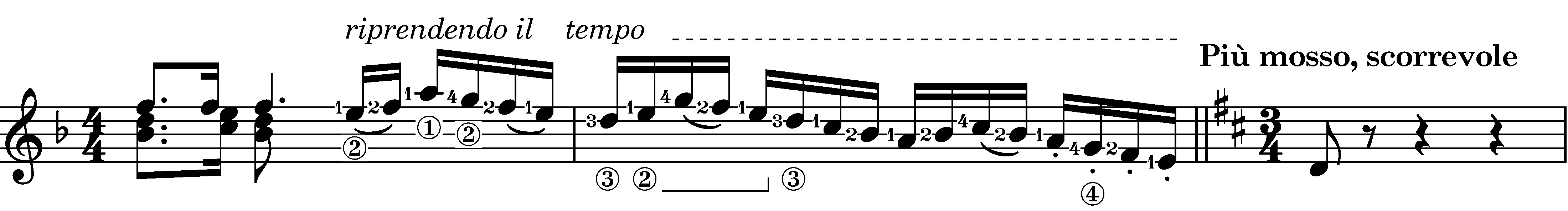

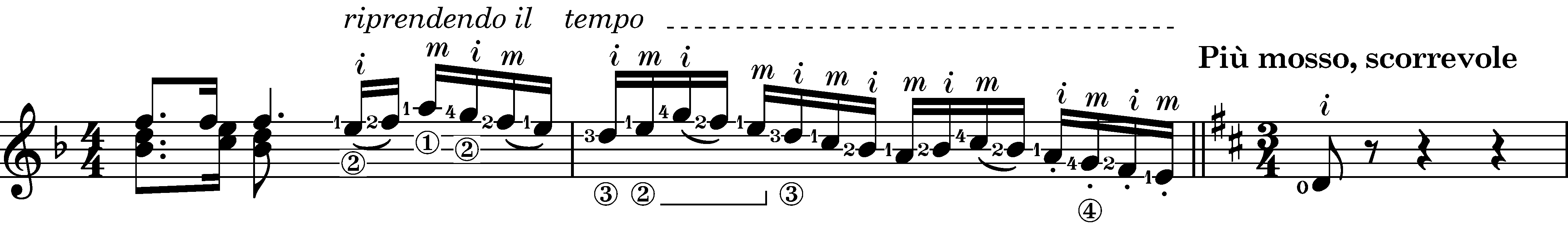

Finally, in Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Capriccio Diabolico from 1935, we find in measures 36 and 37 a short scale passage that serves as a transition between a brief quasi recitativo passage and a faster tempo at the modulation to D major:

Castelnuovo-Tedesco: mm. 36–38, Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85

Once again, no right-hand fingerings are given in the Ricordi edition from 1967, which was edited by Segovia. But if one begins the passage with the index finger, as shown below, all the string crossings work out nicely except for the movement to the fourth string on the last beat of measure 37. Segovia could have fingered the G on the open string, but perhaps he thought the staccato would work better on stopped notes:

Castelnuovo-Tedesco: mm. 36–38, Capriccio Diabolico, Op. 85 with right-hand fingering

Conclusion

Legendary violinist, pedagogue, and author Carl Flesch wrote in his book, Violin Fingering: Its Theory and Practice:[12]

Fingering can be universally valid or individual. In the first instance, it follows definite physiological or musical rules, which have general validity. In the second, it takes into consideration the personal characteristics of the individual performer, the peculiarity of his technical equipment.

He adds that “a practical new edition of a work should contain the fingerings used by the editor in his concerts only if they can claim universal validity. If they cannot, their use will endanger the intellectual independence of the student, even though, for the author, they may represent the most suitable medium for the realization of his intentions.”[13]

Although I find Flesch’s comments thought-provoking, I’m not sure that I know what a “universally valid” fingering would be on the guitar, apart from simple pieces for beginners. There are idiomatic pieces for the guitar and their fingerings might be considered “universally valid.” If Segovia’s fingerings are considered “individual,” it seems prudent to try to discover the reasons behind them before dismantling the relationship between left-hand fingering and right-hand fingering, which would be undone by adding or removing a slur or fingering just one note on different string.

I am not arguing for the inviolability of Segovia’s editions. There isn’t a piece from the “Segovia repertoire” that I’ve performed in which I haven’t made substantial changes to the fingerings. I am arguing, as Chesterton suggests, for one to understand the reasons behind something before deciding to clear it away.

Ronald Sherrod, “A Guide to the Fingering of Music for the Guitar” (DMA Dissertation, University of Arizona School of Music, 1981). ↩︎

Sherrod, 95. ↩︎

Sherrod, xvi. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

BWV 1000 is an intabulation (transcription) for baroque lute of the violin fugue BWV 1001. The manuscript is in the hand of J. C. Weyrauch, one of Bach’s pupils. The version for baroque lute has two additional measures and some textual differences to take advantage of the qualities of the baroque lute. ↩︎

We’ll see examples later in this series of how an understanding of “initiation latency” can help one execute virtuoso passages without departing from the composer’s fingerings. See chapter three of Practicing Music by Design: Historic Virtuosi on Peak Performance for a detailed discussion of “initiation latency.” ↩︎

See Chapter Two of The Classical Guitar Companion for examples and a discussion of historic right-hand fingering practices. ↩︎

John W. Duarte, “Bach on the guitar,” Soundboard, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Winter 1982–1983):, 342. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

G. K. Chesterton, The Thing (London: Sheed & Ward, 1946), 29. (First published in 1929.) ↩︎

Segovia performed a glissando on beat two of measure 78 and beat one of measure 79. The second note of the slide was not articulated by a right-hand finger and I have indicated these with slurs. ↩︎

Carl Flesch, Violin Fingering: its Theory and Practice, trans. Boris Schwarz (London: Barrie & Rockliff, 1966) 6. ↩︎

Ibid. (Emphasis mine.) ↩︎